Margaret Fray

Among her personal belongings, Kathleen Fray left a box labelled ‘Private: Keep Out’. Inside, she had written the name of a hospital near her childhood home where she would have liked to stay once she could no longer live comfortably in the care of her sister, Peggy. But this was not to be: Kathleen died in Grange Hall nursing home in 1997 after a long decline in the sway of Alzheimer’s disease. How she and her family weathered Kathleen’s final years, especially their struggle to find the best possible care for her, form the final chapters of a memorable life story.

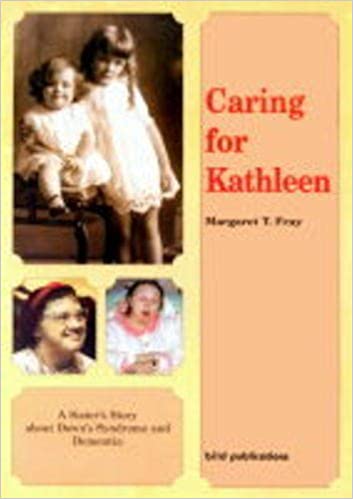

But Caring for Kathleen tells the story of more than one life. Peggy Fray has written about her younger sister Kathleen, born with Down Syndrome in Lancashire, England in 1927. She lived at home with her family for most of her seventy years, and photographs of her parents, sister, friends and festivities enrich the text. The author sets Kathleen’s personal history within the context of vast social changes in her country during years of economic depression, world war, and global realignment. Against the odds,

Kathleen survived a spate of childhood illnesses and infections. Her mother taught her at home, supplementing short periods of village schooling. As a young and middle-aged adult, Kathleen enjoyed socialising and fashion. She spent much of her time in the company of her mother and, later, her sister and brother-in-law. Perplexed at her own clumsiness and mistakes in knitting as she reached her sixties, Kathleen slowly grasped that she was no longer able to manage as she had before. She became increasingly forgetful, dependent on help in every aspect of daily living.

At the time they became her primary carers, Peggy and her partner were 70 and 78, long past the retirement age of most of their peers. Kathleen’s decline in independence was mirrored in the diligent efforts of her sister to find a suitable place for her to live. But those providing for people with intellectual disabilities knew little about the distinctive needs of older people, especially those with Down Syndrome who are more likely to experience Alzheimer’s disease and to do so earlier in life. Nor did hospitals for the elderly welcome patients with intellectual disabilities.

Peggy formed a voluntary association to secure better services and lobbied her MP on behalf of Kathleen and a growing number of men and women with similar needs. Thankful for her own sister’s long life and dignified death, the author pleads for more nurses with specialised training who can care for people like Kathleen.

Leave a Reply